Medical Marvels

VEGASMD

Crystal Dickson

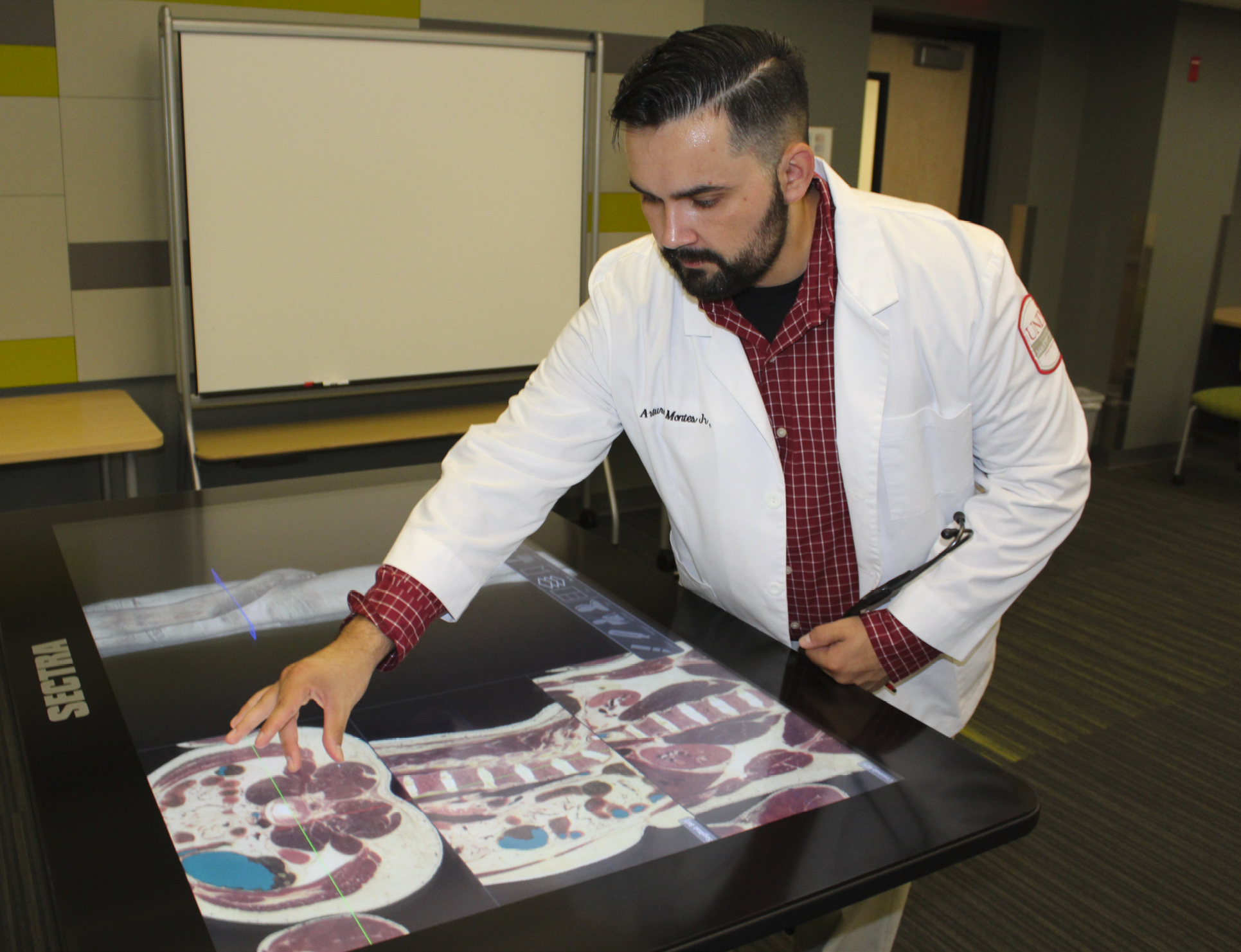

Arturo Montes

UNLV Surgeon Dr. Joseph Thornton preps for surgery alongside RN Eileen Sico.

Story by Paul Harasim

Photos by Paul Joncich/UNLV School of Medicine.

Crystal Dickson, a 23-year-old second year student at the UNLV School of Medicine, remembers…

How, as a little girl, she’d often be left alone by her parents at night, during the day. How, because of their unpredictable behavior, she’d hide in a room or in a closet when they were home. How her parents, sometimes homeless, were repeatedly arrested for use of methamphetamine. How she hated visiting her dad in prison. How other students, as well as adults, assumed she could never amount to anything because of what her parents had done.

The more you talk with this honors graduate of both the Advanced Technologies Academy in Las Vegas and UCLA in Los Angeles – you’ll often find her in the medical school library – the more you realize how wrong it is to assume family background has to dictate a child’s future.

“I remember in high school, when a social worker came...she was talking to me and saw my grade point...it was above 4.0...There was a look of shock on her face. I felt kind of mad. It shouldn’t have been shocking,” she says now. “That attitude is held, unfortunately, by a lot of people. A lot of people assume things that they shouldn’t...when you have parents like mine, people treat you differently and you feel that. A lot of people thought that because my parents had problems with addiction, I would as well.”

Dickson credits her grandmother, an accountant who became her guardian in elementary school, with bringing stability to her life. “She has always encouraged me.”

Crystal Dickson’s story, like that of Arturo Montes and many other students at the UNLV School of Medicine, impresses 72-year-old Dr. Joseph Thornton, an associate professor of surgery at the school, which is now in its second year. “There’s a good mix of students – some with backgrounds you often don’t see in medical schools. I enjoy working with them, teaching them.” Thornton isn’t an easy guy to impress. The son of an African-American single mother in Chicago, he graduated with honors from the University of Illinois-Chicago while working a full-time job in the U.S. Post Office. That background paved the way for his entrance into Nashville’s Meharry Medical School, the first medical school in the South for African-Americans. Thornton argues that a lack of socioeconomic and racial diversity among medical students produces physicians who are not representative of their patients, sometimes serving to exacerbate inequities in access to care.

An Association of American Medical Colleges report found that the median family income of matriculating students nationwide was $100,000 and that a majority of medical students have parents with graduate degrees. Meanwhile, Dr. Sam Parrish, the UNLV School of Medicine Admissions Director, recently found that a quarter of the incoming class at the UNLV medical school are considered economically disadvantaged, generally meaning their families received state or federal government assistance. Nearly half are first generation college students.

Racially/ethnically, about a quarter of both UNLV’s first and second medical school classes are comprised of Latino and African-American students, groups considered underrepresented in medicine. Admission test scores are well above the 500 median score. To help ensure the new school drew quality students in its first year of operation, the school’s dean, Dr. Barbara Atkinson, found donors who provided full tuition, four-year scholarships for the entire 60 student first class. Forty members of the second, 60 member class, received full rides, with the remainder receiving partial scholarships. “Other schools work hard to even hit a target of 10 percent underrepresented students,” says Atkinson, who believes medical school recruitment can contribute to a greater understanding of the backgrounds of all sorts of patients future physicians will care for. Thornton, the first colorectal surgeon in Nevada, says he’s not surprised that Parrish says that admission interviewers have found that students considered “economically disadvantaged” or “underprivileged” seem to have “a fire in the belly” to do well. “They have something to prove,” Thornton says. “Once they see an opportunity is realistic they really go after it. I know very well about that.”

It wasn’t until high school that Crystal Dickson thought she could make a future for herself. “Because of my parents, people don’t expect much from you and you start to feel the same way. But then I noticed if I studied, I could do well in class – People started reacting to me differently when I did well in class – I realized I had the ability to determine my future. In high school, I wanted to have a career in public health or research because I wanted to have a job where I have a positive influence on people’s lives. But becoming a doctor never seemed attainable.”

Her mindset changed after she won scholarships to attend UCLA. There, she majored in neuroscience after her mother was in a car accident and suffered a traumatic brain injury. “In college, my confidence in myself grew and I started volunteering at a neurology clinic. It was while volunteering…taking vitals and talking to patients, that I decided I wanted to become a doctor. I still haven’t decided on a speciality, though.”

During college, she also volunteered with children who came from backgrounds similar to hers. “I spent a lot of time volunteering with foster youth because I wanted children born into circumstances like the one I was born into to know that there was hope and that they do have the ability to improve their futures.”

Today, Dickson lives with her grandmother. So does her mother, who had to get her teeth removed because of the damage methamphetamine did to them. Her father is in prison “because of what he did to get money for drugs...I haven’t talked to him in a long time. I told him the last time he got out of prison that I wouldn’t visit him again if he went back. I hated going to the prison. I had negative experiences there.”

It isn’t unusual to see Dickson carrying two bags of heavy books – one on her back and one on her arm – into the medical school library or virtual anatomy lab. She is passionate about what she believes she can do through medicine to help others, particularly the underserved. That sincere desire – what Parrish refers to as “a fire in the belly,” played a key role in her winning admission. She was awarded the Thomas E. & Mary K. Gallagher Foundation Scholarship.

“I want to help the underserved. I don’t believe that one’s socioeconomic status should determine their health outcomes. I have chosen to become a doctor because there’s something enormously special about being able to have a direct influence on someone’s life and help inspire them to lead healthier, happier lives.”

As Arturo Montes, a 30-year-old second year medical student at the UNLV School of Medicine, walks through the Las Vegas Arts District, he points to the colorful street art impression of the Deadpool comic book character that fills the brick back wall of a downtown building.

“I call what you find on the walls of the buildings down here the art of the people,” he says. These trips downtown, he explains, are one way that he relieves some of the stress associated with medical school, where 40-hour plus study weeks are commonplace.

When Montes was a child, his family of four moved to Las Vegas from East Los Angeles to find jobs. “We were as poor as you can get in America before we moved here. We had little food to eat – tortillas with salt and beans.”

His father jumped at the chance to work 80 hours a week in Las Vegas as a custodian and dishwasher. His mother worked full time as a casino porter.

With his father from Mexico and mother from El Salvador, Montes grew up speaking Spanish. “I didn’t start to speak English until I entered kindergarten.”

As his parents studied to become citizens, Montes became the first in his family to graduate from high school, where he admits he concentrated more on football and wrestling than his studies. “I never even thought of going to college until I was 18.”

It was then his mother suffered a heart attack. “It was devastating. I went to the hospital and she was flatlining.” He watched as a medical team went to work on her and a cardiologist brought her back to life. “Right then, I thought, ‘I want to be a doctor.’ It was amazing. I realized I wanted to help people in much the same way.”

While working as either a busboy or custodian, Montes went to the College of Southern Nevada and then transferred to UNLV, where he graduated with dual majors in kinesiology and biology. Family obligations forced him to work full time before applying to medical school. The full scholarship Montez received to the UNLV School of Medicine came from community leader Randy Garcia, a UNLV graduate and founder of The Investment Counsel Company of Nevada.

“I try to help at-risk youth dream bigger than they probably believe they can,” Garcia says. “I grew up in the old part of Las Vegas, and it was a little dicey. I think mentoring young people to rise beyond their circumstances is what puts the biggest smile on my face.”

Montes plans to follow Garcia’s lead on reaching out to help others. He is well aware that doctors are scarce in Nevada – the state ranks 48th in the number of physicians per capita.

“I love this city more than I can put into words and I want to do all I can for the men, women and children who live in it,” Montes says. “I want to give back to this community, and I want to help the most vulnerable people...there are so many people in this town who need good healthcare, who can do so much more if they just understand opportunities are there.”